Verse in Old English

ᛇ (Ēoh) byþ ūtan unsmēþe trēow,

heard hrūsan fæst, hyrde fȳres,

wyrtrumun underwreþyd, wynan on ēþle.

Translation

Dickins – 1915

The yew is a tree with rough bark,

hard and fast in the earth, supported by its roots,

a guardian of flame and a joy upon an estate.

Discussion

The yew is the first of the four runes named after tree species. While being an evergreen – and therefore technically a soft wood – the wood from yew trees is strong, durable and flexible. This makes it useful for a range of tools, handles, and more famously, for bows (Kilker, 2017).

The first impression the verse gives us of the yew tree is describing its rough bark and appearance. However the rest of the verse contrasts this first impression with the strength and utility of the tree and its wood. This highlights the contrasts between something (or someone’s) first impression, and their true strength and capabilities. This verse therefore encourages us to not judge a book by its cover or people by their first impression. The verse reminds us that if we get past these rough appearances, we will find their real strengths and the joy they can bring. We might not recognise their potential at first look, however once we look closer or underneath the surface, we will find a ‘diamond in the rough’. It is worth remembering that others might therefore miss this if they don’t look close enough. The verse describes the tree as being stable and reliable, while not being flashy. This always brings to my mind the image of an old Landrover Discovery, with their rough and rugged type of dependability.

This ruggedness and dependability can endure. As already mentioned, the yew is an evergreen so keeps its needles all year round, including through the cold of winter. They are also one of the longest lived native species of tree in Europe, the oldest in Great Britain is believed to be between 2,000 and 3,000 years old. While the extraordinary lengths of their lifespans would not have been apparent to the early medieval English, they would almost certainly have known that at least certain yews had been living for generations (Kilker, 2017). Especially as there is evidence that certain trees, including yews, were important places of pre-conversion worship (Pollington, 2011).

This long lifespan adds a sense of timelessness to the virtues and strengths expressed by the yew in the verse. Some have suggested that the Norse cosmic tree Yggdrasil was possibly a yew tree. This adds to the sense of the tree’s support lasting forever, as Yggdrasil survives even Ragnarök. This is also reflected in the description of the tree as the “fire’s keeper”, keeping the hearth alight for a long time.

As the guardian of the hearth fire, the tree helps keep the home (and possibly also the “eþle”, the homeland) going through the rough and the dark. Yew wood burns slowly and has a high heat output, making it particularly valuable wood to burn for a heath or cooking fire (Kilker, 2017). Hall (1977) points out the contrast between the yew being able to support the fire for a long time, with the tree itself being supported by its deep root when in the soil. This is an important reminder that caregivers also need support themselves. Without the roots to keep up the tree while it was growing, it would never have developed enough for the wood to be used in the fire.

The deep roots described in the poem not only provide support, but can also be read as referring to the tree reaching back into its past. This relates to the reference to the tree bringing joy to the “eþel” or “homeland” in the poem. Kilker (2017) paints the image of the tree’s roots reaching across the land to build a connection between the people and where they live. This connection can also be seen as reaching across time as well, to appreciate the history of where you are, and how that history helped shape your life today.

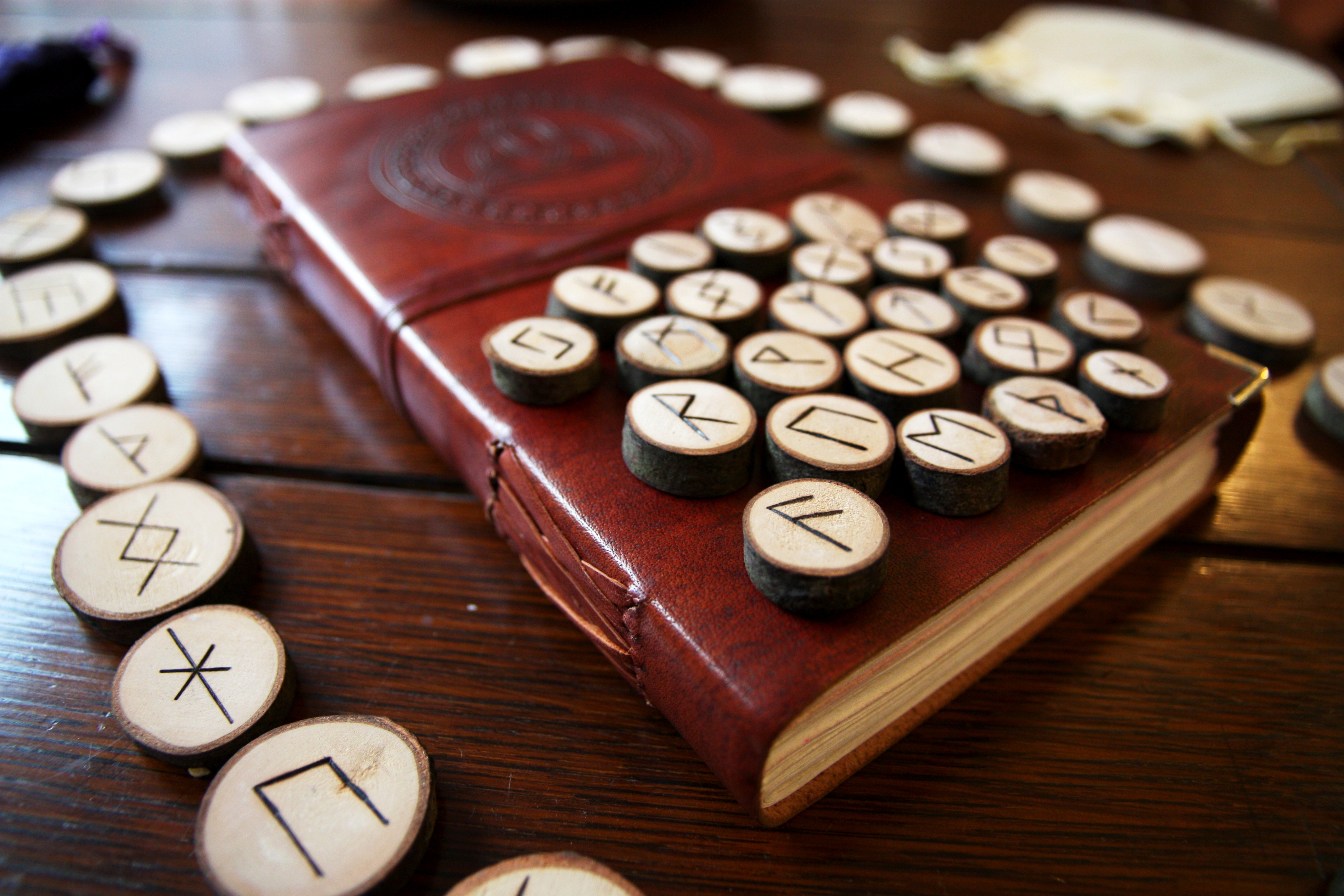

Different yew trees would have been important as community gathering places in their homelands, as also the fires they keep burning would have been central to people’s homes (Kilker, 2017). This gives the yew a sense of centrality and interconnectedness. This is reflected in its place in the rune row. This rune would have been in the middle of the original three aetts of the Elder Futhark. This verse also ends with the phrase “joy to the homeland” or “wyn on eþle”. This contains the name of two other runes, wyn ᚹ from the first aett, and eþle ᛟ from the third aett. Of the final five runes added on the end of the Futhorc, the best bows ᚣ were made from yew. This connects this verse from its central place into the rest of the poem, as the yew tree would have connected the people’s communities.

Kilker (2017) discusses how the yew bow is interwoven with the idea of the warrior from heroic poetry. One of the synonyms used for warriors is “sceotendas” or “those who shoot”. This therefore interlinks the yew with the martial as well as the physical and cultural aspects of the community. Kilker argues that in this way the yew represents protection for the community.

The yew here therefore symbolises the value of all aspects of the community and of their interdependence with each other. This applies to both people’s immediate communities – the ones that they live in – and the wider global communities they are a part of, such as those coming from their relationships to capital and other hierarchies of power. This reminds us of our interdependence with all other people, and the importance of our support and solidarity with each other on a global scale.